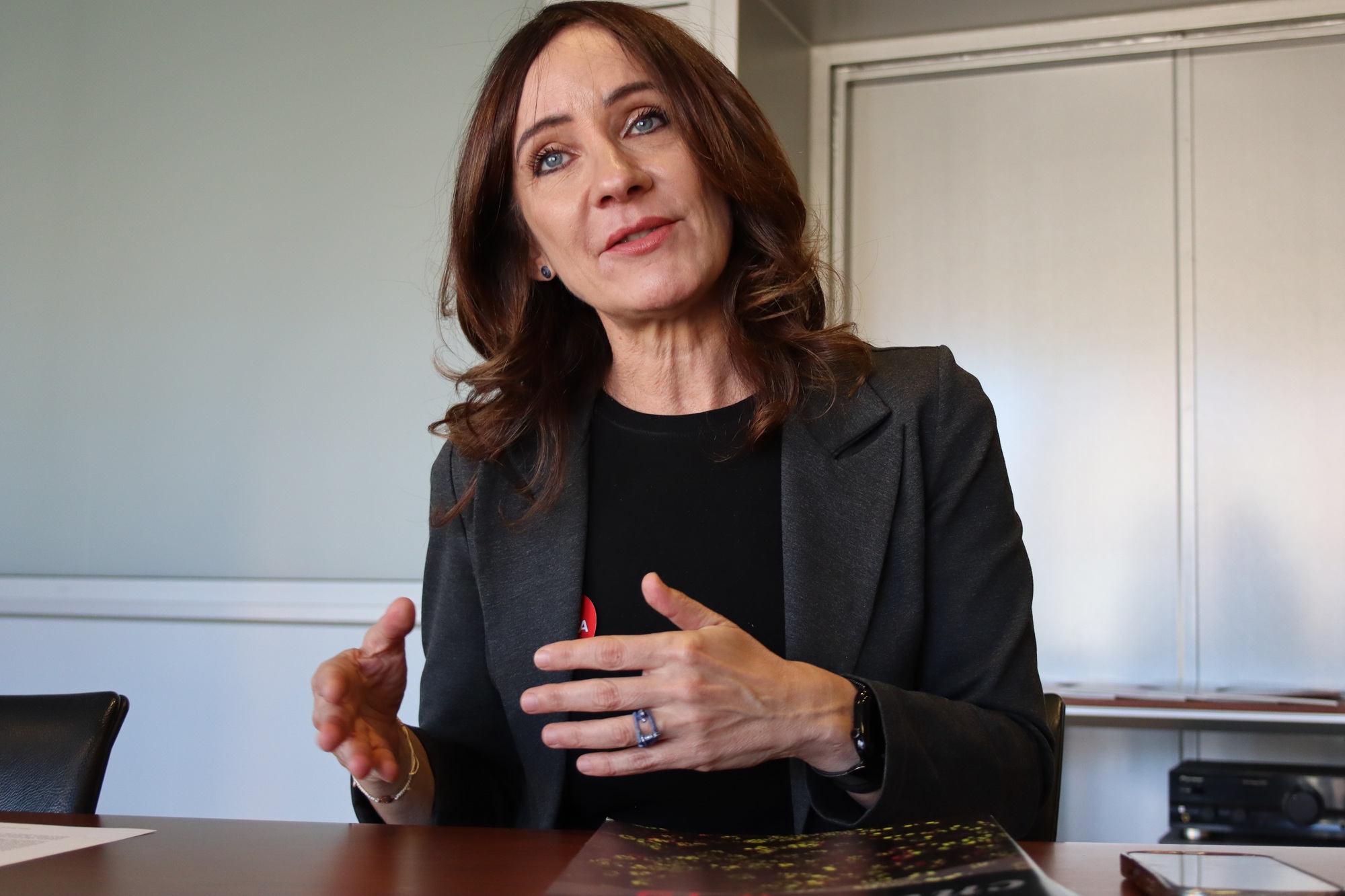

Sabrina Molinaro: “The best choices for public health aren’t always implemented immediately”

Sabrina Molinaro, Psy.D., M.S., Ph.D., is the Director of the Laboratory of Epidemiology and Health Services Research at the Institute of Clinical Physiology of the National Research Council (IFC-CNR), Italy. She leads a multidisciplinary team investigating population health, risk behaviours, and health system innovation. With over 50 coordinated research projects and more than 170 scientific publications, her work bridges epidemiology, data science, and economics to inform evidence-based public health policy. Since 2016, she has coordinated the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD), involving 49 European countries in collaboration with the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Her current research focuses on modelling disease trajectories, integrating AI into precision medicine, and developing econometric tools to evaluate health policies.

- Your research emphasizes integrating diverse disciplines—from psychology and epidemiology to data science and economics. How do you manage interdisciplinary collaboration within your research group to ensure coherent and productive outcomes?

The National Research Council is a governmental organization—it’s not like a university, because we don’t teach; we do research full time. When I started, my first degree was in psychology. I’m not a practicing psychologist now, but I think that foundation is very important. It trained me to look at human behavior and context, even though I realized early on that I wasn’t so interested in individual therapy. I tried it when I was young, but after a few cases, I understood that what fascinated me was not the individual story but the larger design—the behavior of populations.

That curiosity led me to statistics, then epidemiology and public health. I became interested in prevention—understanding not only what goes wrong in individuals, but why certain patterns repeat across communities. My doctoral work was on youth and drug use, and that opened many doors—PhD, postdoc, grants—and, in a way, shaped the trajectory of my career. But I never wanted to stay limited to one topic. Substance use is important, of course, but it’s only one of many risk factors that influence young people’s development. I wanted to look more broadly at health and society.

When I joined the Institute of Clinical Physiology in Pisa, which is similar to CNIC in Spain, my research expanded further. The Institute began as a cardiovascular research center with a small hospital attached. Our director at the time, Dr. Luigi Donato, was a visionary—he started, back in 1997, to collect data on every patient coming to the hospital. Over time, this became a massive database: clinical records, analytical results, imaging data—a kind of early biobank. He also built a data warehouse centered on the patient.

When I joined as an epidemiologist, my role was to make all this information usable for clinicians. That was the second chapter of my career: developing systems that integrate clinical, social, and behavioral data, allowing us to look at health in a 360-degree way. But soon, we realized that clinical data alone wasn’t enough. To really understand people, we need to know about their environment, lifestyle, job, and social context. So, we started to collect survey data on these aspects—what we now call a kind of “statistical twin” of each person.

Today, we talk about digital or artificial twins in health research, but the idea came from this: to build a model that can predict health outcomes by combining biological, behavioral, and social data. Because people’s behaviors—often those associated with “fun,” like alcohol, tobacco, or gambling—are also risk behaviors. Understanding these patterns is key to prevention.

Taxation on these products is still very low, even though their retail price is similar to traditional cigarettes

So, in terms of interdisciplinary collaboration, this is exactly what I do: bring together people from very different backgrounds—psychologists, clinicians, data scientists, economists—and find the common language between them. I often say I’m not an expert at anything, but I can talk with everyone. I’m not a cardiologist, not a psychologist, not a statistician, but I can help them build a model together. That’s what matters, connecting their expertise to understand the whole picture.

- How useful is all this information for public health?

Absolutely, it’s fundamental—I agree with you. The challenge, however, is when you work with governments I often work with various ministries and with the central government and my role is to provide a clear understanding of what is true, what benefits public health, and what doesn’t. But then politics inevitably comes into play, and with it come many other competing interests. So, the best choices for public health aren’t always implemented immediately. That’s where public health research plays a crucial role: it pushes in the right direction.».

For example, in Italy right now, there’s a major debate around electronic cigarettes. Among adolescents—students aged 15 to 19—we’ve seen a significant decline in traditional cigarette use since around 2007. Although there was a slight increase after the COVID pandemic, especially within family groups, the overall trend was downward.

- That’s similar to what we’ve seen in Spain.

Yes, but what’s concerning is that the use of electronic cigarettes and heat-not-burn products has skyrocketed since COVID. As a result, the overall prevalence of nicotine use—both traditional and electronic—has returned to levels we saw 20 years ago. That means we’ve essentially lost two decades of prevention efforts. We spent years educating young people that smoking is harmful, and now they’re turning to these new devices, whose long-term health effects we still don’t fully understand.

This mirrors what happened in the mid-20th century, when traditional smoking became widespread. We’re facing a similar uncertainty now. What we do know is that nicotine is addictive, and tobacco is unquestionably harmful. These new products contain both, and we don’t yet know the full consequences.

Another concern is that many young people start with electronic cigarettes and eventually transition to traditional ones. And we’re having this debate without a clear public health stance against electronic cigarettes. Taxation on these products is still very low, even though their retail price is similar to traditional cigarettes. That means the tobacco industry profits significantly more from these newer products.

We’re actually going to the EU Parliament to advocate for increased taxation on electronic cigarettes. I’m not saying it’s the perfect solution, but it’s a step that acknowledges the potential harm. If we do nothing and remain passive, we’re essentially saying, “Yes, it’s a problem, but it’s also a source of income.”

- Just like traditional tobacco; it’s a revenue stream for governments.

Exactly. And the same goes for gambling. In Italy, gambling generates around €156 billion annually. About 10% of that—roughly €15 billion—goes to the government through taxes. It’s a massive amount of money. We know gambling can be addictive, and while the government does allocate some resources to address gambling-related disorders, it’s like a spoonful of water in the sea—far from sufficient.

Back to tobacco use among youth: I’m not sure about the regulations in Italy, but in Spain, electronic devices are treated similarly to traditional tobacco. In the UK, however, the National Health Service actually recommends electronic cigarettes as a tool to help people quit smoking. I’ve had interesting discussions with colleagues from the UK about this. If we know these devices are harmful, why are they being recommended?

- So, it seems to be a scientific and medical debate, with no universal consensus.

I completely understand. My response to those who advocate for harm reduction is this: if someone is a heavy smoker—say, 20 traditional cigarettes a day—then switching to electronic or heat-not-burn products might be a reasonable step. It’s not ideal, but it’s better than continuing with traditional cigarettes. That’s harm reduction.

But that’s a very different scenario from young people who are just starting to smoke. They’re not switching from 20 cigarettes a day, they’re starting with electronic devices and then moving on to other substances. And when we talk about flavored electronic cigarettes—papaya, mango, milk and mint—what are we really talking about? Have you ever met a heavy smoker who smokes milk and mint-flavored cigarettes?

It’s not reasonable. It’s not about quitting—it’s about marketing to young people. And that’s a serious public health concern.

- You also study social phenomena like Hikikomori—social withdrawal among young people. How does that fit into your research?

Yes, the Hikikomori phenomenon started in Japan in the 1990s, and I remember reading about it as a student, thinking, “This could never happen in Italy.” But now, our national student survey shows that around 2 4% of Italian students exhibit similar behaviors—severe social withdrawal.

These young people spend most of their time isolated in their rooms—sleeping, eating, studying, and gaming alone. Parents often don’t realize it’s a problem, because they think their child is “safe” at home, away from external dangers. But over time, isolation becomes total, and it’s very hard to reverse.

Part of the issue is societal: today’s young people live under high pressure, constantly controlled, and often find more comfort in the virtual world than in real social interactions. Over time, even those virtual connections fade, and they withdraw completely. This is not just a youth issue—it’s a reflection of the society we’re building.

- If you had unlimited time and funding, what would you most like to study in the future?

I would like to develop models to monitor how our society is changing, using what we call the exposome approach. The exposome integrates all kinds of influences on health: behaviors, environmental exposures, genetics, and clinical data. My dream is to create a comprehensive model for prevention—one that helps us anticipate future risks before they become widespread.

Because we know populations are aging. That’s good, but only if people age in good health. If we become a society of fragile, chronically ill elderly people, that’s a challenge for everyone. So, I want to contribute to building a future where people live long, healthy, and active lives—where they are a resource, not a burden.

It may sound idealistic, but that’s my motivation: to help people stay healthy through better understanding, better data, and better prevention.