Molecular Regulation of Heart Failure

Decoding Genetic Cardiomyopathies: From Genes to Therapies

Our group has expanded its research in genetic cardiomyopathies by working directly with families affected by severe inherited heart diseases, thanks to our close collaboration with clinical cardiologists and geneticists. This partnership allows us to address real clinical challenges through experimental biology to tackle cardiac conditions for which no cure currently exists. By combining cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) with CRISPR-engineered mouse models, we investigate how newly identified genetic mutations alter cardiac function. Through advanced techniques such as echocardiography and electrocardiogram, we uncover how these variants disrupt the heart’s structure, function, and electrical activity, providing crucial insights into disease mechanisms.

Figure 1. Mutation p.S358L in TMEM43 induces biventricular dysfunction and accumulation of fibrofatty tissue in the myocardium. WT, wild type mice; TMEM43wt, mice overexpressing the wild type version of human TMEM43 in cardiomyocytes; TMEM43mut, mice expressing the mutant version of human TMEM43 in cardiomyocytes. Full paper here.

This cross-disciplinary approach also allows us to explore new therapeutic options for the affected families, especially gene therapy. Moving beyond the traditional one-size-fits-all paradigm, we are committed to developing personalized therapies using cutting-edge CRISPR-based approaches and adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors, which hold promise for correcting or modulating disease-causing mutations. As part of these efforts, we have recently developed a gene therapy for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy caused by the S358L mutation in the gene TMEM43. We also developed a gene therapy for the treatment of arrhythmogenic/dilated cardiomyoyathy caused by truncating variants in the gene FLNC. We were the first to use CRISPR activation (CRISPRa)in vivo for a heart disease. While these therapies have been tested in mice so far, our aim is to translate these results to the clinics so that patients can benefit from them.

Our efforts are further strengthened by national and international collaborations, including our participation in the European DCM-NEXT network, which seeks to advance targeted treatments and deepen our understanding of the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying dilated cardiomyopathy.

Video 1. Expression of TMEM43 with the p.S358L mutation results in severe cardiac contraction. The video shows echocardiographic images of the left ventricle in the longitudinal axis (please note the resolution of the video has been reduced). WT, wild type mice; TMEM43wt, mice overexpressing the wild type version of human TMEM43 in cardiomyocytes; TMEM43mut, mice expressing the mutant version of human TMEM43 in cardiomyocytes. Full paper here.

The alternative heart: How Post-transcriptional Regulation Breaks the One gene–One protein Rule

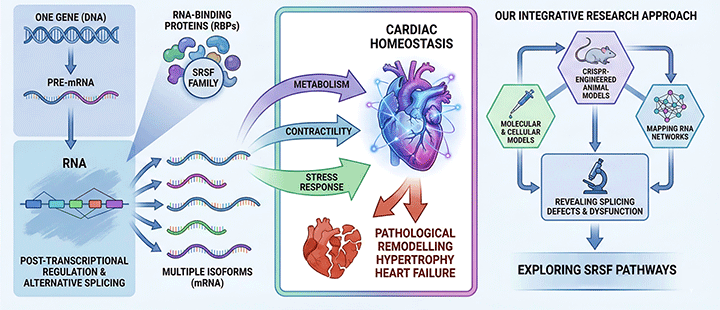

We often learn that one gene makes one protein, but biology is far more flexible and complex. Through alternative splicing, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) can turn a single gene into several protein isoforms, each with its own function, structure, localisation and/or role. In the heart, these different isoforms help fine-tune metabolism, contractility, and the ability to withstand stress. When this regulatory system slips out of balance, the heart can drift toward pathological remodelling, hypertrophy, and eventually heart failure.

Our research focuses on the serine/arginine-rich splicing factor (SRSF) family, a group of RNA-binding proteins that coordinate RNA splicing, stability, and localization, to maintain cardiac homeostasis. When SRSF-mediated regulation goes awry, the resulting shifts in the transcriptome disrupt cellular balance and drive disease. Although these pathways have been extensively studied in cancer, their impact on the heart remains largely unexplored.

Figure 2. Schematic representing our approach to study the role of SRSF proteins in the heart.

By integrating molecular, cellular, and CRISPR-engineered animal models, we map how SRSF proteins shape RNA networks in cardiomyocytes, revealing how splicing defects contribute to metabolic and structural dysfunction. In this context, we have recently reported that the regulatory axis composed by SRSF4 (an RBP), GAS5 (a non-coding mRNA) and GR (a transcription factor) controls cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic function. In contrast, the loss of SRSF3 in mouse hearts results in severe contraction defects due to alternative splicing of the master metabolic regulator mTOR.

A prime example of how post-transcriptional regulation can change the localisation and function of a protein and thereby reshape cardiac biology is calcineurin, a protein with which we have been working for many years and which never stops surprising us. While its canonical isoforms activate NFAT and promote hypertrophy, our work showed that the alternative Calcineurin Aβ1 isoform improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction and reduces myocardial hypertrophy. This illustrates beautifully how distinct isoforms emerging from the same gene can have opposing physiological roles.

Getting ahead of heart failure: From Early Signals to New Therapies in HFpEF

Our lab studies the molecular mechanisms that regulate the development of heart failure. Heart failure is the ultimate consequence of heart disease and it basically represents the inability of the heart to pump blood in an efficient manner due to the lack of proper heart contraction or relaxation. We have a strong interest in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which is characterised by relaxation defects and accounts for half of the heart failure cases worldwide. HFpEF has rapidly become one of the most pressing challenges in cardiovascular medicine: a growing global burden, and a major unmet medical need. There is no effective treatment for HFpEF and it is difficult to diagnose accurately. In our lab, we have developed translational mouse models that develop HFpEF naturally with old age. We have shown that while different diseases (comorbidities) contribute to HFpEF, the road they follow to heart failure is different, indicating that HFpEF is not one condition but many.

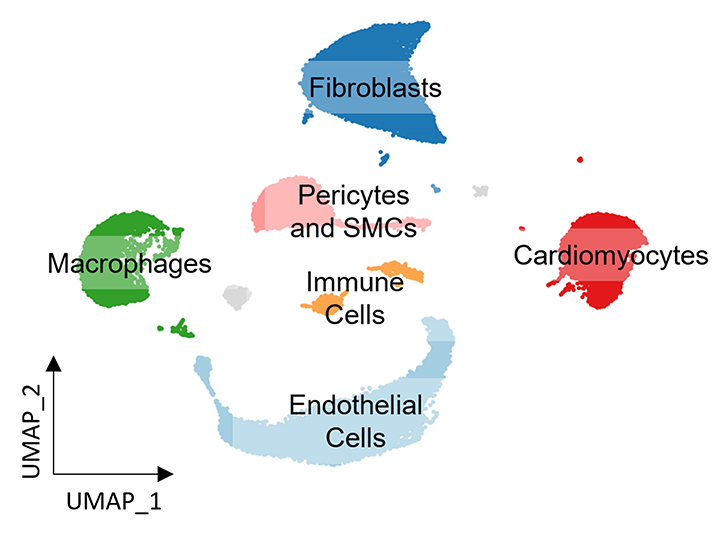

Figure 3. Mapping cellular heterogeneity in the mouse heart with snRNA-seq.

Building on this foundation, we are now focused on uncovering the earliest molecular events at the subclinical stage, with particular emphasis on the contribution of metabolic diseases, which have emerged as the dominant drivers of HFpEF. Our goal is to identify new biomarkers, reveal actionable molecular pathways, and open the door to innovative therapeutic strategies.