Ellie Tzima: "Genuine interest and enthusiasm are essential; skills can be learned, motivation cannot"

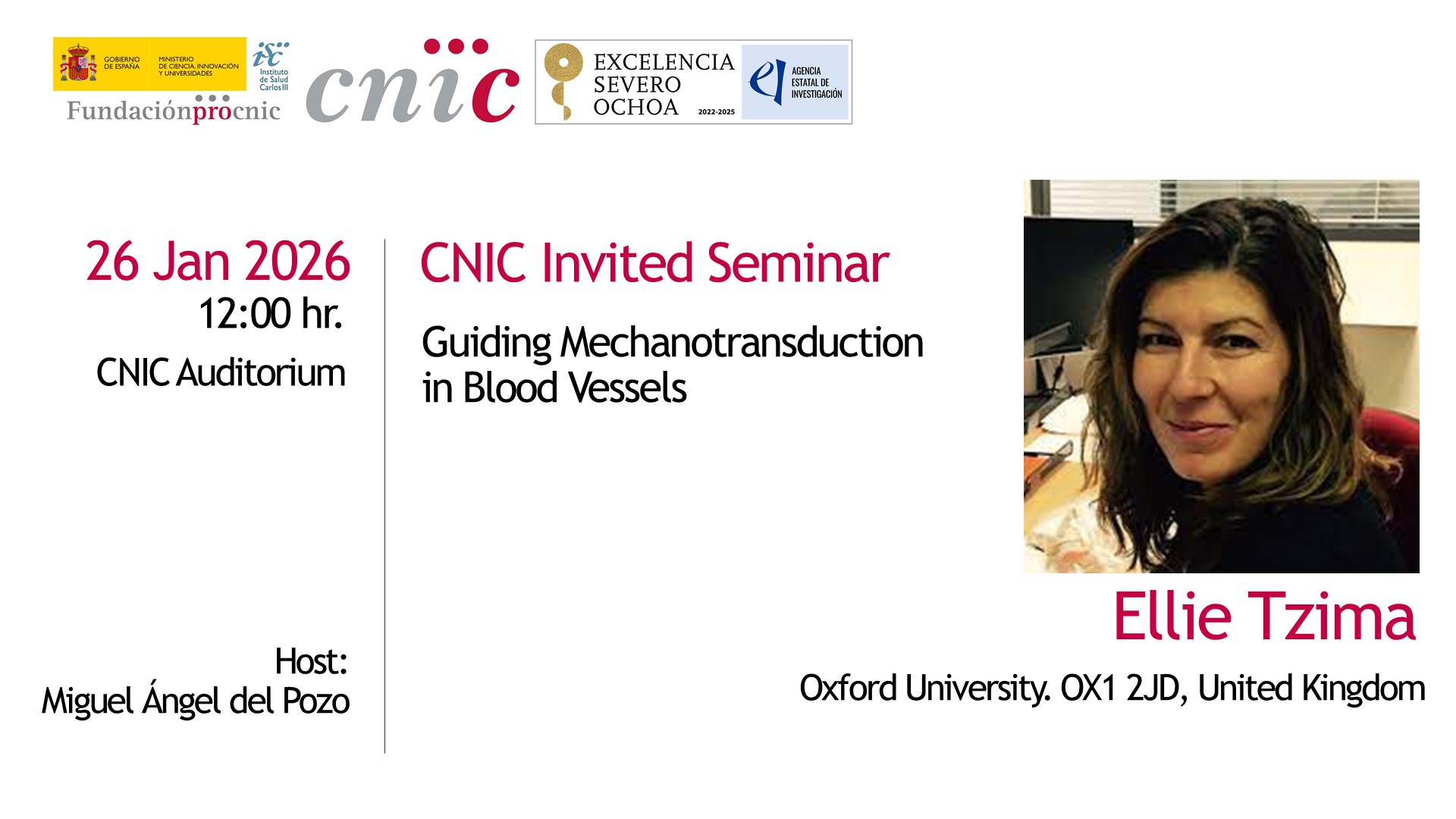

Ellie Tzima is a Wellcome Senior Fellow and Professor of Cardiovascular Science at the University of Oxford; positions she has held since 2015. Before that, she spent a decade as Assistant and Associate Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She completed her postdoctoral work at the Scripps Research Institute, where she discovered the junctional mechanosensory complex — a major contribution to vascular biology. Tzima has led NIH-funded projects, served on editorial boards of Circulation Research and ATVB, and received several prestigious awards. She currently works on the UK Medical Research Council Review Panel. Her lab studies how mechanical forces regulate cardiovascular function. They have developed one of the most comprehensive models of endothelial mechanotransduction to date. Her recent work identifies a new class of mechanosensors that explains why atherosclerosis develops in specific regions of blood vessels.

- What is the main question your lab is trying to answer?

These are always the hardest questions to summarize. At the moment, we are trying to understand why atherosclerotic plaques develop only in specific regions of our blood vessels. If you look at lipid- and cholesterol-rich plaques in human arteries, you’ll see they are not uniformly distributed — they appear in very focal areas. This localization is strongly linked to irregular blood flow.

Just like in a river: in straight segments, flow is uniform and smooth, and disease does not develop there. But in bends, where whirls and eddies form, the flow becomes turbulent — and turbulent flow promotes disease. We want to understand why that is: how blood vessels detect the type of flow they experience, how they communicate this information to neighboring cells, and how this ultimately leads either to protection or to disease. It’s a fundamental biological question with very significant clinical implications.

- Because I understand this happens in all patients, always in the same places. Do you know why?

Yes — turbulent flow triggers chronic inflammation. Combined with systemic risk factors like high cholesterol or hypertension, this primes blood vessels for plaque development. Endothelial cells become sticky, attracting circulating cholesterol and leukocytes, which initiates inflammation and, over time, plaque formation.

- What technologies do you use to study this?

We use live cultured cells and specialized systems that can simulate both turbulent and steady, protective blood flow. We also work with genetically engineered mice and rely heavily on microscopy. In addition, we use a broad range of omics technologies — single-cell approaches, proteomics, and more — which are essential today.

- Once you understand why this happens, will prevention be easy?

Prevention is difficult to imagine, especially because atherosclerosis begins in the first decade of life — we won’t be giving medications to children. Instead, we aim to develop therapeutics that interrupt the mechanosensing of turbulent flow. These drugs could be used together with statins: one to lower cholesterol, the other to block harmful mechanosensing.

A plaque itself isn’t necessarily dangerous; the problem arises when it ruptures and blocks blood flow to the brain or heart. If we can stabilize plaques by interfering with mechanosignaling, they can remain harmless. Delivering drugs locally is another major challenge, but promising technologies are emerging.

- Why is it important to understand how blood flow controls signaling in blood vessels?

If we understand how turbulent flow is sensed and how it triggers disease, we can selectively interrupt those harmful pathways while preserving protective ones. Distinguishing between different flow patterns and the signaling networks they activate is crucial for developing targeted therapies.

- What are the main goals of the projects funded by the European Reseach Council (ERC)and Leducq Foundation?

Both projects involve mechanosensing but in very different contexts.

ERC is a collaboration between four groups: a neuroscientist, a vascular biologist, a nanoscientist, and us — mechanobiologists. Starting next month, we will study the blood–nerve barrier in peripheral nerves, which is far less understood than the blood–brain barrier.

- What is the blood–nerve barrier?

It’s the interface between blood vessels and neurons in the peripheral nervous system — essentially all the nerves in our limbs. It is clinically important: peripheral neuropathies, carpal tunnel syndrome, nerve injuries requiring regeneration, and chemotherapy-induced neuropathy all involve disruptions in this barrier.

Peripheral nerves experience constant mechanical stimuli — every touch, every movement. We want to understand how mechanical forces regulate the blood–nerve barrier in health and how this signaling becomes disrupted in disease. Our role is to investigate the mechanosignaling, while other groups study nerve function and vessel–neuron communication. Ultimately, we plan to design nanoparticles capable of interrupting pathological mechanosignaling to treat peripheral pain. It’s an ambitious project.

- How difficult is it to work with all these different people?

We haven't officially started yet, and even the preparation has been challenging. We come from very different disciplines and even use different vocabularies. We spent a week in Paris preparing for the interview, working side by side to craft a joint presentation. Our styles were completely different — I prefer minimalistic slides, while another collaborator includes everything — so we had to find middle ground. It was humbling but also a lot of fun.

This collaboration will take us into areas of biology I would never have explored alone, and that’s extremely exciting.

- Did you find a common language?

Yes. We developed a shared style for writing, presenting, and answering questions. We also coordinated who would answer which type of question, especially the unexpected general ones.

- And Leducq Project?

This project focuses on peripheral arterial disease (PAD), which is related to atherosclerosis but affects arteries in the limbs, like the femoral artery. Statins are less effective for PAD patients, and severe cases can lead to limb amputation.

Our hypothesis is that cell stress and mechanosensing are essential for forming collaterals — natural bypass vessels that can reroute blood flow around blockages. Clinical trials using VEGF, a molecule that promotes new blood vessel formation, have failed because VEGF alone is insufficient. We propose that combining VEGF with mechanosensing pathways could synergistically promote collateral growth and restore blood flow.

- You work across many areas and lead a large team. How do you keep up?

Two things help. First, I have excellent long-term team members who understand the system in depth and help train newcomers. Second, despite the different projects, they all share a common theme: endothelial mechanosensing. Each tissue adds its own “flavor” through specific molecular players, but the core mechanisms remain the same. Once you understand the core, the variations become manageable — like adding accessories to a good outfit.

- Did you always want to be a scientist?

Yes. I wasn’t good at much else, and I never wanted to do medicine.

– But your work is closely related to medicine.

It is, but we focus on discovery. Medicine applies these discoveries to patient care. My daughter is training to be a doctor and agrees — doctors apply knowledge, while we uncover how diseases arise in the first place.

- Some scientists pursue pure knowledge; others seek application. Where do you stand?

Both matter. Applications help communicate why we do what we do, but curiosity is essential. Many breakthroughs began with curiosity-driven research. We must continue funding it.

- How do you select and train new researchers?

I don’t have a rigid system. Personal interaction is key — if communication doesn’t flow during the interview, it won’t work in the lab. My team also meets candidates and shares their impressions, which I value highly.

Genuine interest and enthusiasm are essential. Skills can be learned; motivation cannot.

- Do most applicants have this curiosity?

Often, yes. But Oxford can also attract people who want the name on their CV rather than the science. It doesn’t happen often, but we stay vigilant.

- How difficult is it to be a good mentor?

It’s an ongoing process. I often learn from how other labs operate. I also try to pass on the opportunities my mentors gave me, even if students don’t always appreciate them immediately. You don’t do it for gratitude — you do it because mentorship should be passed on.

- Do you think the turbulent international political situation is affecting science?

Brexit affected us significantly. We now have far fewer EU applicants because visas and work permits are barriers. The US political landscape hasn’t affected students much, but more US group leaders are considering moving to the UK, which used to be rare.