Travis Hinson: "Those of us in research and medicine have a duty to educate better, to be more honest, more open, and more transparent"

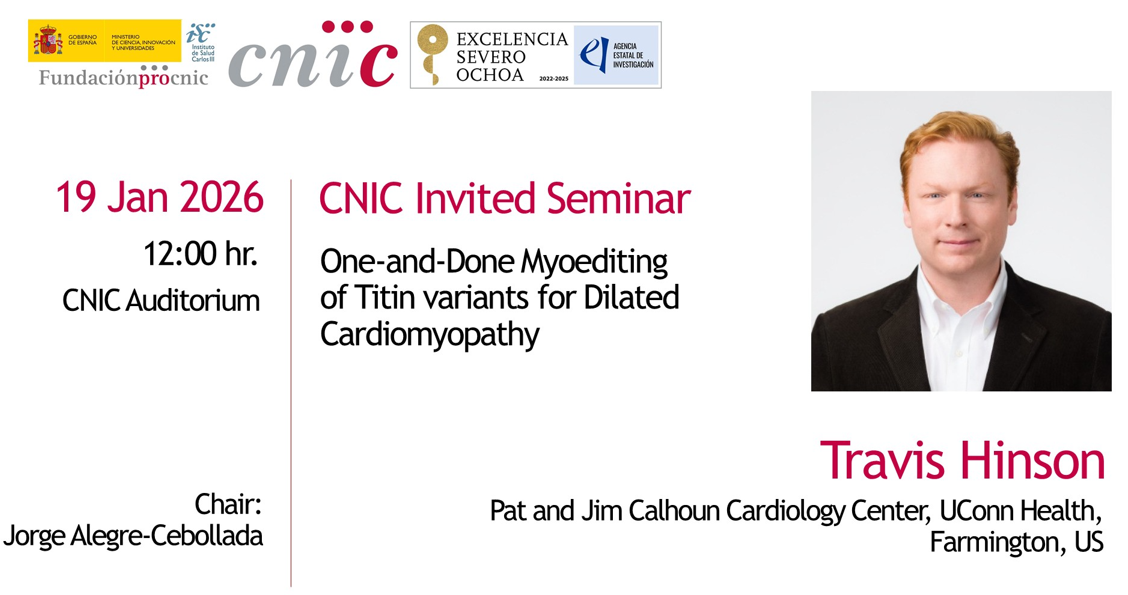

Dr. Travis Hinson is an NIH-funded physician–scientist and clinical cardiologist specializing in inherited cardiovascular diseases. He is the Jim Calhoun Endowed Associate Professor of Cardiology and Genetics at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine in Farmington, Connecticut, a precision medicine genomics institute. He also serves as Founding Director of Cardiovascular Genetics at UConn Health, where he provides clinical care for patients with inherited cardiovascular disorders. Dr. Hinson’s research focuses on developing best-in-class human and animal models of cardiovascular disease, integrating human stem cell biology, tissue engineering, microphysiological systems, genome editing, and mouse models. His laboratory is advancing a next generation of genome editing–based therapeutics aimed at treating inherited cardiovascular diseases that remain inadequately addressed by current therapies. Dr. Hinson received his M.D. from Harvard Medical School, completed residency training at Massachusetts General Hospital, and completed a Fellowship in Cardiovascular Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

- You are a medical doctor but not a PhD in science. How, where, and when did you start to be interested in science, in basic science? Because when I read about you, most of your work seems to be in basic science.

When I was in secondary school, I loved science, and I thought I was actually going to be an engineer. The reason I liked engineering was because science was applied to important problems for people. I was around a lot of people in the chemical industry, so I decided to do chemical engineering.

I started university thinking I was going to be an engineer. In the U.S., you enter university and you can change direction. During my first year, I worked in the summer at a chemical engineering company, and I realized it was not a good fit for me.

At the same time, I had a research experience in a biological engineering group doing tissue engineering on artificial vascular grafts, and I really enjoyed that. So I decided to switch into medicine.

I did it because I always loved science, but instead of engineering, I felt that in medicine I could apply science directly to human life and suffering. From the beginning, I loved scientific discovery, and medicine allowed me to do that for patients and in a disease-oriented way.

In the United States, you first do undergraduate studies. I did mine in chemistry and then applied to medical school at the end of undergrad. I then went down the path of doing research as an MD.

My mentors only had MD degrees. Christine Seidman, for example, was one of my mentors; she is a cardiovascular genetics researcher and also did research without a PhD. She told me that you can get the training you need as an MD by supplementing with fellowships. So I always integrated research into my training, not through a formal PhD, but through other routes.

I’ve always been interested in science and medicine because it allowed me to apply science to human disease and suffering. Science has always been my ultimate interest.

- You probably have the best of both worlds: you enjoy your research, and you also see patients. That way, you can take questions that arise in the clinic and try to solve them in the lab.”

Yes, I’m a firm believer that when you immerse yourself in a problem, you want to see all aspects of it. As a clinician, I see patients directly: what their hearts look like on imaging, what heart failure looks like clinically, what the treatments and complications are. That experience inspires me to work harder in the lab and gives me perspectives on questions you might not think about without clinical exposure.

The clinical side provides excitement and a clear sense of importance because I see people suffering, but it also gives me unique perspectives on research questions.

A lot of my work is guided by the ultimate goal of impacting people. There is a spectrum: some fundamental work focuses on basic cellular and molecular processes, which are extremely important, but I’m not as well trained to study those in isolation. I try to study processes that are closer to human disease.

So I’m on the translational side. Even though I do basic research, it always has disease or human relevance, partly because of my clinical experience.

- What do you mean by “reading” the genetic code of heart failure, and how do genomic approaches improve our understanding beyond traditional cardiology models?

I think “decoding” is the perfect word. Imagine I come in and I don’t speak Spanish at all. When I hear Spanish, I hear sounds and grammar, but I don’t understand the meaning.

The genome is similar. We see letters, spelling, grammar, and rules, but if we don’t understand them, it’s just noise. Decoding means turning that noise into meaning.

It’s like wartime codebreaking, listening to encrypted messages and trying to make sense of them. We’re trying to take a very complex genetic code of billions of nucleotides and distill what it means for patients. It’s ambitious, but we’re trying to play a small part in that process.

- How do you figure it out?

One of our main goals is designing experiments that help us decode that meaning. If we find a genetic variant—a misspelling—and don’t know what it does, we can build a system in a cell or a mouse that contains only that variant and study its effects.

We can see how it affects force production, gene expression, or cellular markers. By isolating one change and observing its consequences, we can decode its function.

- But you decode something very specific. How do you translate that to something bigger, like a tissue, an animal, or a human?

That’s a great point. We know the general functions of many proteins, especially those involved in heart contraction and pumping. The diseases we study are ultimately about too much or too little pumping.

We build cellular systems focused on that readout, but cells alone aren’t enough. So we use tissue engineering and other technologies to make systems that are more physiological and integrative. The heart has many cell types, and we try to incorporate that complexity.

We know what heart failure looks like in patients from imaging and clinical data, and we try to connect that to what we see in cells and tissues.

I often use a car analogy. The sarcomere—the structure I study—is like the engine. You can have too much horsepower or too little. Either is bad. You need the right amount for the car. If the engine is too powerful, you wear out the tires and brakes; if it’s too weak, the car doesn’t move properly.

Genetic changes can cause too much or too little “horsepower,” and our goal is to identify and correct that imbalance, using gene therapy or drugs.

- What technologies do you use to understand this complex scenario?

We create engineered heart tissues from human stem cells, three-dimensional mini heart tissues with human cells and a biophysical environment similar to the real heart. We use microfabrication and semiconductor technologies to build them.

We study calcium flux using advanced microscopy, use echocardiography to image mouse hearts, and apply next-generation sequencing and proteomics for molecular characterization.

We also use genome editors, which allow us to introduce patient-specific variants into our models and potentially correct them therapeutically.

- Once you have decoded the genetic code of heart failure, how close are you to rewriting it?

Rewriting is definitely a goal. There are two main approaches. One is directly correcting the variant using CRISPR-based technologies. The other is correcting the consequence of the mutation.

For example, if a mutation causes reduced protein production (haploinsufficiency), we can activate the gene to increase protein levels without fixing the mutation itself.

We now know patient sequences, we can identify harmful variants, and we have tools to safely rewrite or compensate for them.

Twenty years ago, developing a therapy required massive pharmaceutical infrastructure. Genome editing has changed that; it puts therapeutic development into the hands of geneticists and physician-scientists. This is a golden era for people like me.

- Cardiovascular disease is a global pandemic. Do you think these technologies will change the scenario in the next 10–20 years?

Globally, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death. Public health interventions—blood pressure control, diet, addressing obesity—are likely to have the greatest impact in the next 10–20 years.

Genetic therapies will show proof of concept in that timeframe, but they will initially be expensive and limited to small populations. Over time, they’ll become cheaper and more accessible.

Public health measures are still the most impactful, but genetic therapies will mature and eventually contribute significantly.

- Do you still see patients?

Yes, every Wednesday I see patients in a precision cardiovascular clinic. We evaluate suspected genetic cardiovascular diseases -heart failure, arrhythmias, aortic disease, early heart attacks-.

We help identify genetic risks not just for patients but for their families. Often, by the time the first patient presents, the disease is advanced. But identifying family members early allows prevention and early treatment.

Genetics shifts medicine toward prevention at the family level, which is far more effective.

- Do you think governments should do more to promote healthy habits, given that many people don’t believe obesity or hypertension are serious risks?

Physicians need to do a better job of education. Nutrition is very hard to study, which leads to conflicting advice. In the U.S., the influence of the food industry on politics is a real problem. Your director, Dr. Valentin Fuster, has been a strong proponent of education; I’ve heard he even has a Sesame Street puppet. That’s an example of using a children’s TV show to educate people at a very young age about the importance of good health care, and I think that’s very important.

One thing I would emphasize about nutrition is that it is not an easily researched field. It’s very difficult to study, and as a result, it leads to what I would call heterogeneity in advice. I think the current situation in the United States reflects this.

First of all, it’s very important that companies do not have so much influence over government policies and recommendations. In the United States, the food industry has a significant influence on politics. This represents a missed opportunity for physicians to advise the government more effectively. The reason is that when physicians try to do so, the food industry pushes back, because they make money by selling products. As a result, there is too much corporate influence in U.S. politics.

- I think it's the same here in Europe.

But I think it’s worse in the United States. I don’t know much about European politics, but what I can tell you about the United States is that lobby groups essentially represent industry, whether it’s the dairy industry, the beef industry, tobacco, or others.

Historically, these groups fund politicians, and as a result, politicians who receive funding from those industries are often hesitant to speak out or vote against them. Until money is taken out of politics, it will always be an uphill battle.

I also think it goes both ways. Another important issue that you didn’t mention is that vaccinations are under attack in the United States, which is crazy.

- It's unbelievable.

Truly unbelievable. However, I can understand how vaccine companies have historically developed vaccines: when you run a clinical trial, the vaccine works, just like a drug.

Like drugs, the medications we use are generally tested in robust clinical trials involving large populations, with clear measurements of outcomes. The way this works is that we look at averages: on average, people benefit from the drugs that are approved. However, it’s inevitable that some individuals will experience serious side effects. For example, in a trial of 10,000 people, maybe five have a severe adverse reaction, while 100 people benefit. If you are one of the five who experience that side effect, it understandably feels like a very bad outcome for you.

Vaccines work the same way. If you run a clinical trial with 20,000 people, on average the vaccine is protective and helps the population. However, there may be a small number—say, five people—who develop an autoimmune condition. The current administration is focusing on those few cases and shaping policy around them, rather than considering the overall benefit to the population. Personally, I don’t think that’s the right approach.

At the same time, I also don’t think it’s right for governments to claim that vaccines have absolutely no side effects. They do have side effects. But on average, the benefit is far greater. The problem is that scientists and doctors have not always educated the public in a balanced and honest way.

All we really need to say is this: if a million people receive a vaccine, on average they are going to live longer. However, we cannot rule out that three or four people may develop an autoimmune disease, and we won’t know in advance who those people will be. So you are much more likely to benefit than to be harmed, but there will still be some adverse events. We need to be honest about that.

Sometimes public health has the right goal—which is to promote vaccination—but the messaging can be flawed. We also need to acknowledge that perhaps one in 10,000 people may develop a condition such as a polyneuropathy or something like multiple sclerosis. Even so, the overall outcome is much better for the population.

I think we need to give people more credit and assume they can understand nuance. When we don’t communicate honestly and someone experiences a complication, trust is lost. We saw this during COVID. People were told they would be “cured,” but then some individuals—such as teenage boys—developed myocarditis. In most cases it resolves on its own, but we weren’t transparent about that risk.

We should have said: yes, this may happen in a small number of cases, but it is still far better than not being vaccinated. Or we should have explained that vaccination reduces severity rather than guaranteeing immunity. Instead, people were told, “Once you get it, you’re fine.” When they then got infected again, trust eroded, and that loss of trust led people to support voices that focus only on the rare adverse cases.

The point I’m trying to make is that those of us in research and medicine have a duty to educate better—to be more honest, more open, and more transparent. Transparency is key.

- You mentioned the COVID vaccines; these companies are not especially transparent.

No, they’re not, and they’re also legally protected. In the United States—and in many cases worldwide—you generally can’t sue vaccine manufacturers if you experience a serious adverse event. They are largely immune from liability. There is a legitimate reason for this: without that protection, vaccine companies likely wouldn’t have a viable business model, and we need vaccines. So that immunity was granted for a reason.

However, today that immunity is often perceived differently. Because the pharmaceutical industry funds politicians, it can appear as though companies are paying for immunity so they can sell large volumes of drugs. That creates the perception of a conflict of interest. While there is a legitimate rationale behind liability protection, we need to be honest about it, discuss it openly, and be transparent. That’s my opinion, and it’s a very complex issue.

People no longer see diseases like measles, so they forget how serious they are. We know what will happen: vaccination rates will drop, measles and other severe diseases will return, and then people will say, “Okay, now I want the vaccine.”

This pattern repeats itself. We’re at one point in the cycle now. When people start to see the negative consequences again, they’ll change their minds. And then, 30 years later, the same thing will happen again. When there’s no measles, mumps, rubella, or hepatitis B, people become complacent. When these diseases reappear, they realize why vaccines were necessary. Humans forget, that’s just how we are.